In a follow-up to the December 2017 Living Labs edition of the environmental SCIENTIST, Filipa Ferraz devises a Living Lab analysis in a university context that raises the importance of integrating university roles, groups and layers.

Living Lab’s potential as a method

In recent years, a number of researchers have sought for an answer to how universities could encourage sustainable development beyond the activities inside the classrooms. Activities that could present the university as a ‘stage’ of sustainable practices, showing society how to tackle environmental, social and economic issues by holistically applying their resources within their own space and people.

One of the routes explored to achieve this objective was through the use of Living Labs, as they provide exactly this - an opportunity to trial new practices in an everyday environment.1,2,3,4 More specifically, the early definitions of Living Labs characterize them as “experimental platforms that function as ecosystems where the users are studied in their everyday habitat and subjected to a combination of research methodologies while testing new technologies under development”.5 This definition has since evolved and has now been translated as a method where innovation is best achieved through co-design and co-creation,6 with great potential for sustainable innovation.7

The Institution of Environmental Sciences (IES) and the Committee of Heads of Environmental Sciences (CHES) published an edition of the environmental SCIENTIST journal in December 2017, championing the various merits applied in universities and exploring the method in several different contexts and formats.

|

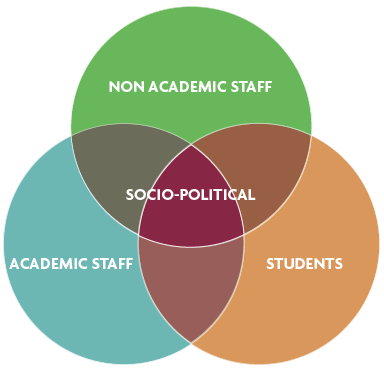

| Figure 1. The university groups (© Filipa Ferraz) |

The importance of focusing on Community

My own research is taking a deeper view of internal university stakeholders (among other aspects), and it is using the modern Living Lab design as support. Through this view, the university stakeholders are defined as Campus Community. The idea is to determine how people act individually, as well as in groups, and the different power structures that can be associated with them.

Beyond the physical environment, it is the stakeholders who greatly contribute to the ‘Lab’ to be ‘Living’ and indeed their contribution should not be overlooked as to do so could result in a laboratory experiment that is faulty.8 Therefore, the wants and needs, as well as the power plays between these actors, become truly relevant in the design of any Living Lab.

As the research developed, two problematic areas also emerged that further reinforced the importance to focus on stakeholder interactions inside the university setting:

- the organisational structure of universities seems to lead to strict divides between people, contributing to miscommunication and conflict when projects dedicated to more sustainable practices are being trialled;9,10,11 and

- the recurrent complications with the management of stakeholder relations (their needs and expectations) in Living Lab projects, is also related to the drop-out rate of stakeholders engaged at the beginning of a Living Lab project compared to the end.12,8

In basic terms: if the needs and expectations of stakeholders are not properly planned for during a university Living Lab project, they will likely waste their time decoding communications or walking into conflicts. Not only does this time-loss increase the management of relations for the project team, but it could also directly result in stakeholder drop-out, leading to weaker results or even failure of the project.

The Campus Community structure

In an effort to define the Campus Community, let’s start by describing its environment – the universities. Although widely varying in terms of size, type of degrees and even historical, cultural and social background, a university can generally be described as a place where:

- individuals study to achieve an academic degree and partake in research;

- classrooms and laboratories support lecturers with teaching, students with learning and researchers with exploring their ideas; and

- the classrooms, laboratories and other resources are managed by a number of different staff in administration and operations.

With this general (and non-exhaustive) description of university activities and spaces, it is possible to see how actors emerge in groups of students, academic staff and non-academic staff, providing the initial form of the Campus Community. Among these actors, there are those who interestingly have overlapping roles. They are included in an interlinking group defined as the Socio-Political (Figure 1). The characterisation of this group acknowledges not only that roles can overlap but also the considerable power that governance activities can leverage in the institution, for instance, those activities dedicated to boards, committees or unions, where the individuals have a dual responsibility. Practical examples of these roles are:

- a facilities supervisor that decides to go back to education and enrol in an MSc Degree - Non-Academic – Academic overlapping;

- when a student is also a student union representative - Academic – Governance overlapping; or

- a professor that is also responsible for operations management at the senior level (a Director for Operations) - Academic – Non-Academic overlapping.

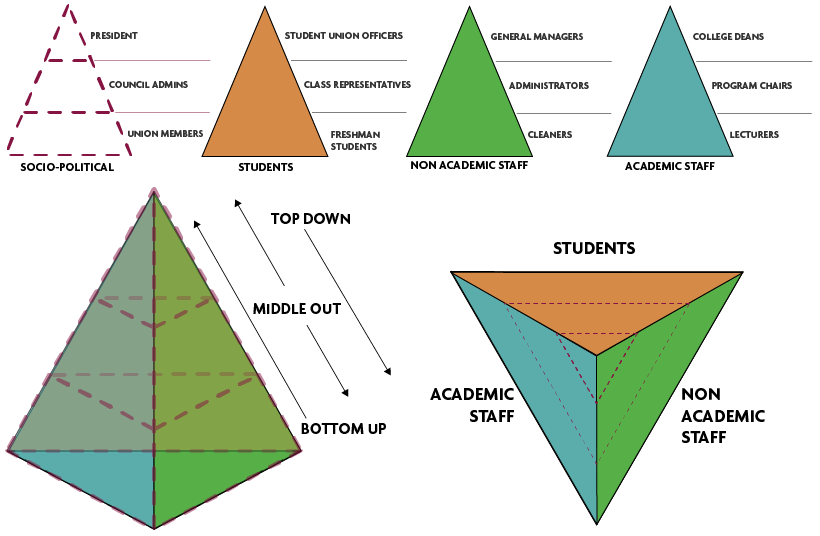

As mentioned earlier, different research has shown that power plays and organisational divides can have a great impact on how effective projects are developed inside university campuses. To analyse where these issues could surface, the Campus Community definition integrates a separation of potential strategic forces inside the university (see Figure 2).

There are three potential strategic forces defined in the Campus Community:

- Top-down – the senior leadership that decides on main strategies, approaches and priorities in an institution;

- Middle-out – the individuals that are responsible for applying decisions taken by the above group. Their power resides on how specifically the decisions are applied onsite; and

- Bottom-up – the layer composed by the base of all groups, their power can reside:

- in numbers, more specifically, how much influence a large group of individuals can have over the other two; and

- in particular groups or individuals that through dedication and very targeted actions can create influence over how decisions are applied onsite.

|

| Figure 2. Campus Community Power Levels (© Filipa Ferraz) |

The Living Lab format and the integration of the Campus Community concept

The location of my Living Lab is the Greenway Hub (Figure 3), the first new building of the Grangegorman Campus at the Technology University Dublin (TUD), currently under construction.13 When finalised, the new campus will have infrastructure suitable for 20,000 students and staff, making it one of the biggest campuses in Ireland, as well as a great location to investigate a variety of issues related with sustainability (infrastructure, organisational change, educational impact, etc.).

The Greenway Hub is promoted as the first building on campus that follows a number of different environmentally friendly specifications,14 which is one of the main reasons why it was chosen as a base for the Living Lab. Following the choice of the base, the research design established the building shall serve the research in two ways:

- firstly by providing sustainable technology for analysis; and

- secondly by analysing how the different Campus Community stakeholders of this building work with and around the technology.

Therefore, the data that is being collected generally relates to sustainable infrastructure management (more precisely, the technology for water management from solar power and rainwater harvest), and the actions and perceptions of the Campus Community in the building.

The focus of this article relates to the second point – Campus Community – and therefore it is important to highlight how this particular data is being collected. The Campus Community of the Greenway Hub is associated with sustainable technology through two services: hot water for washing hands and utensils and grey water harvesting for toilet flushing.

|

| Figure 3. The Greenway Hub (© DIT Foundation) |

How does the campus community associate with the services? Well, some are the people who use the services, “users”, and the remaining are the people responsible for implementation, monitoring and maintenance of the same services “providers”. Through a series of interviews, surveys and observations, the data relevant to actions as well as perceptions of both users and providers will be collected (note: this method will be in a testing phase until April 2020).

With this plan, the service providers and service users can be part of different groups (see Figure 1), and across the different layers in the organisation (see Figure 2), hence forming a representative section of the whole Campus Community. Furthermore, with this plan the behaviour analysis around the use, management and maintenance of sustainable technology will be possible, as well as the thinking behind its initial implementation.

In summary, the research plan shall enable an institutional analysis of sustainability practices, with a very small amount of resources.

This research methodology might be simplifying the analysis of big, intricate and complex organisations. Nonetheless, the design is clearly trying to engage with the “Ivory Tower” complex universities are labelled with,15,11 striving to unfold power structures that potentially complicate project development, including those projects encouraging sustainability. More importantly, the objective of the research design is to create a Living Lab method that can be applied in any university, one that acknowledges where barriers are likely to emerge, but also where drivers towards sustainable practices exist and should be amplified.

Filipa Ferraz is a PhD researcher at the Technological University Dublin. Her research explores Organisational Change of universities towards more sustainable strategies which was triggered after a nearly two year experience as a coordinator of environmentally friendly strategies, linking different stakeholder groups within a Higher Education context and amplifying these links with businesses and NGO’s outside the higher education walls. She has project managed European Funding coordination proposals focused on themes that varied from “Improving Behaviour Indicators for Sustainability through Gaming initiatives” to “Marine Spatial Planning cooperation links for Europe’s Blue Growth”. This experience led her to facilitate stakeholders from five to eight European countries at every project ranging from academia, government authorities and industry. She is a member of the Dublin Food Co-op’s Board of Directors, where she is dedicated to the improvement of the internal organization’s structure of one of the oldest co-op in Ireland.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/filipa-ferraz-2016036b/

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Filipa_Ferraz3

To read more about Living Labs, check out the living labs edition of the environmental SCIENTIST

1. Verhoef, L. A. et al. (2018) Towards a learning system for University Campuses as Living Labs for sustainability, Universities as Living Labs for Sustainable Development: Supporting the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals - Volume 2. Springer, ed. Leal, W. et al., 2018 (in press).

2. Vezzoli, C. and Penin, L. (2006) Campus: “lab” and “window” for sustainable design research and education: The DECOS educational network experience, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 7(1), pp. 69–80. doi: 10.1108/14676370610639254.

3. Evans, J. et al. (2015) Living labs and co-production: University campuses as platforms for sustainability science, Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2015.06.005.

4. Robinson, J. (2016) Making a Difference Universities as Living Labs and Agents of Change. EAUC. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K1dvtdEvHD8.

5. Niitamo, V. P. et al. (2016) State-of-the-art and good practice in the field of living labs, 2006 IEEE International Technology Management Conference, ICE 2006. doi: 10.1109/ICE.2006.7477081.

6. Pallot, M. et al. (2010) Living Lab Research Landscape : From User Centred Design and User Experience towards User Cocreation, Technology Innovation Management Review. doi: 10.1007/s001170000531.

7. Keyson, D. V, Guerra-Santin, O. and Lockton, D. (2017) Living Labs, Design and Assessment of Sustainable Living. Netherlands: Springer. Springer.

8. Habibipour, A. et al. (2017) Drop-out in Living Lab Field Tests: A Contribution to the Definition and the Taxonomy, Open Living Lab Days 2017, Krakow, Poland, pp. 7–20.

9. Alshuwaikhat, H. M. and Abubakar, I. (2008) An integrated approach to achieving campus sustainability: assessment of the current campus environmental management practices, Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(16), pp. 1777–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2007.12.002.

10. Ramos, T. B. et al. (2015) Experiences from the implementation of sustainable development in higher education institutions: Environmental Management for Sustainable Universities, Journal of Cleaner Production. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.05.110.

11. Ávila, L. V. et al. (2017) Barriers to innovation and sustainability at universities around the world, Journal of Cleaner Production. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.025.

12. Georges, A., Schuurman, D. and Vervoort, K. (2016) Factors affecting the attrition of test users during living lab field trials, Technology Innovation Management Review, pp. 35–44.

13. TUD Greenway Hub. Available at: http://www.dit.ie/greenwayhub/ (Accessed: 1 February 2019).

14. TUD Grangegorman Campus Development - Home. Available at: http://www.dit.ie/grangegorman/ (Accessed: 1 February 2019).

15. Creighton, S. (1998) Greening the ivory tower: Improving the environmental track record of universities, colleges, and other institutions. MIT Press.

Header image: Grangegorman campus | William Murphy | Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)