environmental SCIENTIST | Science without borders | September 2017

The health of the ocean is inextricably linked to human wellbeing, and fisheries are vital for food security, livelihoods and the sustainable development of billions of people worldwide. In 2014, fishery exports from developing countries were valued at US$80 billion, higher than all other food commodities (including meat, rice and sugar) combined1. However, the protection of this resource is an ongoing challenge for the global community. Since 2009, the percentage of overfished stocks worldwide has hovered around 30 per cent1, and poorly managed fisheries have contributed to the degradation of marine ecosystems around the world.

While recent research highlights the efforts of fisheries in developed countries to improve sustainability, significant challenges remain, particularly in the developing world where 73 per cent of seafood is caught2. In this context, restoring ocean health and ensuring the sustainable use of marine resources requires a holistic approach, drawing on science and environmental conservation as well as addressing social and economic challenges. The United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water) can’t be achieved without considering the other UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, or Goals) which encompass the alleviation of poverty, hunger, and poor working conditions and the promotion of economic growth, sustainable consumption and climate action. Equally, ending overfishing has been identified as a pre-requisite to achieve many targets across the Goals3.

Credible certification and eco-labelling programmes are one tool with applicability across a broad range of the Goals and are part of the solution for ending overfishing globally2.

The Marine Stewardship Council

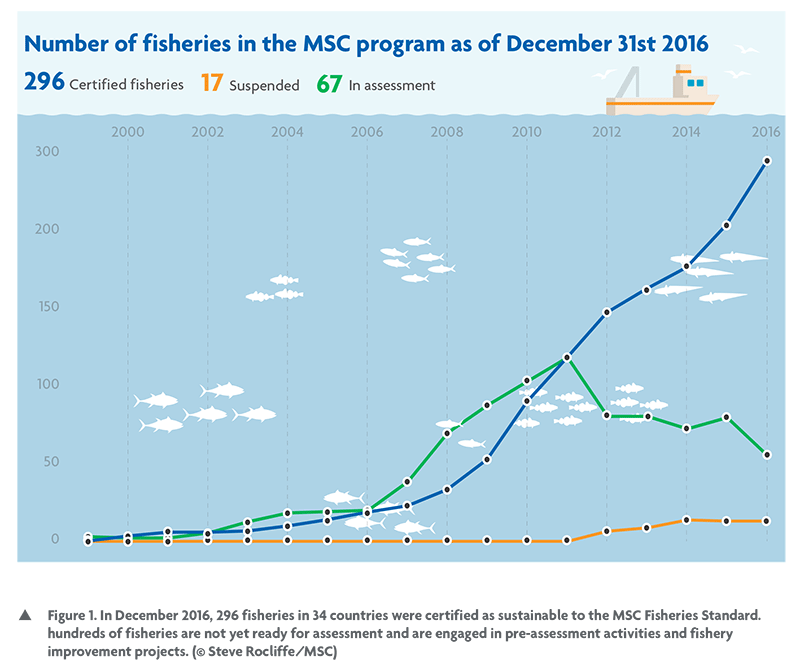

The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) is an international non-profit organisation established to address the problem of unsustainable fishing and safeguard seafood supplies for the future. The MSC is widely recognised as a leader in wild capture certification, with 12 per cent of global marine catch currently certified.

The MSC’s science-based ecolabel and fishery certification program contributes to the health of the world’s oceans by recognising and rewarding environmentally sustainable fishing practices and influencing the choices people make when buying seafood. Our theory of change holds that consumer desire and market demand for products bearing our ecolabel encourages fisheries to achieve MSC certification, and that the efforts of these fisheries to demonstrate sustainability result in positive change on the water.

As part of the Concept Paper on Partnership Dialogue 4: Making Fisheries Sustainable at the UN Ocean Conference, the MSC program was recognised as a promising tool for developing partnerships and sustainable seafood supply chains4. One example of a global partnership supported by the MSC is the ‘Seafood Business for Ocean Stewardship’ initiative. Led by the Stockholm Resilience Centre, the initiative connects the global seafood business to science in support of Goal 14 and includes an ocean stewardship pledge from 10 of the world’s largest seafood companies5.

By incentivising best practice in the fishing industry, the MSC contributes to several of Goal 14’s targets including ending overfishing, implementing ecosystem management, and eliminating illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing6.

In 2016, the largest ever global analysis of attitudes to seafood consumption was carried out on behalf of the MSC. The research found that sustainability is a key driver for seafood purchase. Across 21 countries, sustainability was rated as more important than price and brand, with 72 per cent of seafood consumers agreeing that in order to save the oceans, shoppers should only consume seafood from sustainable sources11.

In order to restore overfished stocks by 2020 and achieve the targets set within Goal 14, recent research from the FAO concluded that greater emphasis must be placed on replicating successful sustainable fisheries policies from developed countries across to the developing world2.

Lucy Erickson is the Science Communications Manager for the Marine Stewardship Council and formerly a freelance writer based in the fishing village of Mũi Né, Vietnam. Lucy holds an MSc in Biodiversity, Conservation and Management from the University of Oxford.

(Email: lucy.erickson@msc.org | Twitter: @lucye__ @MSCecolabel)

This article is taken from the September 2017 edition of the environmental SCIENTIST.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2016) The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. <www.fao.org/3/a-i5555e.pdf>

- Ye, Y. and Gutierrez, N. L. (2017) Ending fishery overexploitation by expanding from local successes to globalized solutions. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1, 0179.

- Singh, G. et al. (2017) A rapid assessment of co-benefits and trade-offs among Sustainable Development Goals. Marine Policy, in press. 4. United Nations (2017) Concept paper - Partnership Dialogue

- Making Fisheries Sustainable. United Nations Ocean Conference, New York, 5-9th June 2017. <https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/14418Partnershipdialogue4.pdf>

- Seafood Business for Ocean Stewardship. <www.keystonedialogues.earth>

- ISEAL Alliance and WWF (2017) SDGs mean business – how credible standards can help companies deliver the 2030 agenda. <www.standardsimpacts.org/sites/default/files/WWF_ISEAL_SDG_2017.pdf>

- Marine Stewardship Council (2017) Global impacts report. <https://www.msc.org/documents/environmental-benefits/global-impacts/msc-global-impacts-report-2017>

- The World Bank (2009) The Sunken Billions: The economic justification for fisheries reform. <https://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTARD/Resources/336681-1224775570533/SunkenBillionsFinal.pdf>

- Lallemand, P., Bergh, M., Hansen, M., and Purves, M. (2016) Estimating the economic benefits of MSC certification for the South African hake trawl fishery. Fisheries Research, 182, pp.7-17.

- Kittinger, J. et al. (2017) Committing to socially responsible seafood. Science, 356 (6341), pp.912-913.

- Marine Stewardship Council (2016) Seafood consumers infographic. <https://www.msc.org/documents/msc-brochures/msc-consumer-survey-2016-infographics-eafood-consumers-put-sustainability-before-price-and-brand>

- Brackley, A. and Lee, M. (2017) Evaluating Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals: A GlobeScan/SustainAbility Survey. <www.sustainability.com/our-work/reports/evaluating-progress-towards-sustainable-development-goals>