environmental SCIENTIST | The Impact of Environmental Science Research | November 2015

The theme of research impact was extensively discussed in the November 2015 issue of environmental SCIENTIST. For the purposes of the UK government’s Research Excellence Framework 2014 (REF 2014), a peer-assessed audit of university research expertise, researchers in environmental sciences and all other recognised disciplines submitted evidence of significant impact from their findings in almost every country of the world. Environmental science is, to a large extent, a mission-oriented discipline in which researchers endeavour to develop an understanding of, and solutions to, environmental challenges at all scales. The wide variety of types of impact claimed by participants in REF 2014, potentially benefitting both the natural environment and the quality of human life, testify to this.

However, at first reading there is remarkably little translation of high-quality environmental research into measures to enhance the environmental performance and sustainability of universities themselves. We looked at data from two sources: the analysis of basic REF 2014 scores for research achievements in earth systems and environmental sciences, and the rankings achieved by host universities in the People & Planet University League tables1 . Our preliminary analysis suggests that many of the leading research-intensive universities are not using their scientific expertise to enhance their own sustainability ratings and environmental performance.

This article explores the nature of this disappointing lack of local impact and recommends that as higher education institutions (HEIs) increasingly focus on the international influence of their research, they should not forget to look at how they may be able to make a difference closer to home.

The people and planet university league

The Oxford-based network People & Planet has been supporting UK students in campaigning on the linked issues of poverty, human rights and the environment since 1969. It started compiling an annual league table that ranked universities on their environmental and ethical performances in 2007. Previously called the Green League, the People & Planet University League assesses every UK organisation that is legally registered as an HEI and receives public funding1.

Each institution is asked to respond to a set of questions, which in 2015 embraced fourteen sustainability topics (see Box 1). The answers are assessed by a trained team of People & Planet staff and volunteers on the basis of the information returned2; raw scores are weighted by section (using a methodology explained in full on the People & Planet website3) and a summary ranking derived. The list of questions has been extended and tightened up over the years in consultation with experts from within the environmental and higher education sectors, and the remit of the League has extended into new realms. Whereas the early questions included recycling percentages, renewable energy use, environmental auditing and Fairtrade status, the more recent surveys have requested additional information on student curricula and ethical investments, for example. Non-responding institutions are typically included as Failed Universities, whilst the remainder are graded according to UK undergraduate degree classifications from First Class to Third.

The organisers state that 37.5 per cent of all questions may now be answered using data taken directly from annual estates management statistics, routinely collected and published by the UK Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA). The remaining questions are sent out as a survey issued as a freedom of information or environmental information request, to which universities have ten weeks to respond. Unfortunately, in 2014, there was evidence that many universities found the process unusually burdensome and the timescale for response inconvenient, so a number boycotted the process. The complainants also cited deficiencies in the methodology and disagreement with the weighting of different criteria. From 2015 assessors are being allowed to search for missing data themselves if universities have not responded fully. The dataset is far from perfect as a measure of institutional sustainability, but is probably sufficient to provide a rough guide.

As well as being a means by which HEIs can be compared and tracked on their sustainability activities and commitments, the People & Planet University League offers some incentive for universities to improve their own performance on ‘green’ issues. Indeed, some remarkable progress towards sustainability across the sector can be identified. For example, for all of the 2007 survey respondents, average renewable energyuse on campuses was around 12 per cent, whereas by 2013 the figure had risen to approximately 75 per cent as universities shifted to suppliers with explicit commitments to renewables, and some began to use their own facilities to generate power from anaerobic digestion of food waste, wind turbines or solar panels. Some institutions also pressed ahead with experimental power generation by drawing on the research expertise of their academic staff, but this type of cogeneration of power and knowledge was unfortunately very restricted. It cannot be claimed that People & Planet’s League tables were the sole influence on environmental performance, but they certainly provided a stimulus to some decision-makers.

Who performs well?

The early stars of the 2007 League tables were Leeds Metropolitan, Plymouth, Hertfordshire, Glamorgan and Gloucestershire Universities, which surprised many readers, including in some cases the institutions themselves: many of the highly rated institutions turned out to be those whose principal focus was on teaching rather than on internationally celebrated research. Those rated as First Class nevertheless included four research-intensive universities from the Russell Group, the loose federation named after the London hotel where their vice chancellors used to meet. The four were Queen’s University Belfast, Cambridge, Edinburgh and Leeds.

In the 2015 rankings, although several Russell Group institutions did receive First Class scores, the highest ranked was in 12th position, which was Newcastle University. Leeds kept its First Class status, Edinburgh moved to 2:1 Class, and both the University of Cambridge and Queen's University Belfast received only Third Class scores4.

In recent years the rankings have continued to be dominated by newer universities whose principal focus has been on teaching rather than research. Why this should be the case is an interesting question, especially when many of the low-scoring universities are academic homes for experts undertaking world-leading research on environmental themes. We are not asserting that the term ‘environmental science’ is synonymous with the sustainability that People & Planet purports to measure, but we do believe that good science is an underpinning requirement for strong sustainability, and that environmental scientists have some moral commitment to environmental improvement. Indeed, the Institution of Environmental Science’s own Code of Professional Conduct5 makes reference to members being required to have “full regard for the enhancement of environmental quality and sustainable development and the mitigation of environmental harm”. In our experience this principled stance is widely found across the sector.

Comparing people and planet with REF 2014

Taking the People & Planet rankings for 2013, the year in which universities were required to make submissions to REF 2014, we can compare in more detail the rankings of HEIs in the League with their performance in the Earth Systems and Environmental Science category (unit of assessment 7) of REF 2014. Though this assessment of research expertise is contested as a source of useful information (and certainly as a basis for determining future research funding from central government), it does provide a broadly consistent measure. Research in environmental sciences is bundled with earth sciences to provide one unit of assessment.

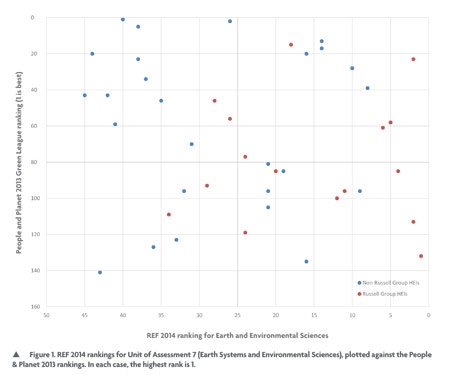

Figure 1 shows the ranking based on REF 2014 scores for unit of assessment 7 (for those universities who made submissions) plotted against 2013 People & Planet rankings. The REF 2014 scores are largely weighted towards the quality of research outputs in terms of originality, significance and rigour, but also include a 20 per cent weighting for impact and 15 per cent weighting for contribution to the research environment6. If expertise gained through high-quality research was being effectively translated into strongly sustainable institutional practice and environmental initiatives, we would expect to see a positive association between these two variables, with highly rated institutions concentrated in the top-right quadrant and low-rated institutions lacking such research expertise in the lower left. However, in Figure 1 it is difficult to identify any association at all.

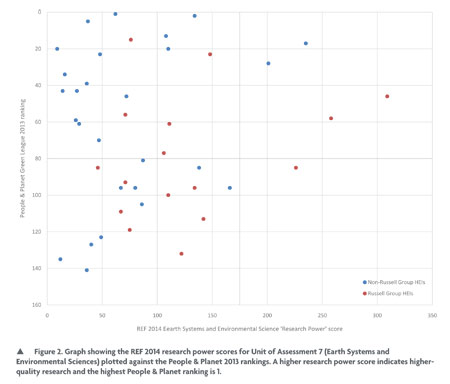

Looking exclusively at research quality, Figure 2 plots People & Planet rankings against an index of research power. Again there seems to be no positive association, suggesting that the production of high-quality environmental research is largely disconnected from institutional sustainability.

Wicked problems

The data presented here highlight a clear disconnection between environmental research and local practice in UK universities. The environmental science expertise and knowledge being generated in many of our world-leading institutions is not being applied to enhance their own performance on environmental and sustainability policies, on institutional resource use (energy, power, goods and services), or in stimulating students’ interest and achievements. Perhaps local challenges are not being posed to researchers in academic departments as research questions demanding solutions? Or potentially, the research-intensive institutions do not find local sustainability challenges to be a mechanism for generating respect in research. Whatever the cause, this detachment must diminish our efforts and ability to address environmental challenges, not just on university campuses but in wider society.

The universities performing well in the People & Planet tables do not share any particular geographical attributes, or (at least in the 2015 breakdown) approaches to other characteristics such as an arts focus or a Church foundation. They do, however, tend to be institutions that have made the transition to university status more recently. It could be proposed simplistically that one reason for their more sustainable performance is the centralised managerial cultures that are found in these institutions: with a committed vice chancellor or chief executive, and a compliant culture, action follows. It is possible that the strong local community links of the former polytechnics and colleges of higher education are also a factor in delivering on-campus sustainability goals. These observations are of course highly generalised, and individual institutions will have their own views on their own achievements and challenges.

However, many of the environmental challenges we face can be described as ‘wicked problems’7. These are complex problems characterised by a large number of conflicting or contradictory views and evidence that are usually not resolvable through consensus. In tackling these problems, we amplify the challenge through lack of effective communication. This seems to be at the root of the disconnection between expertise and action in many of our HEIs.

The path to sustainability

In research-intensive HEIs, such as those in the Russell Group, academic independence is fiercely defended. We should not underestimate the importance of this freedom in delivering high-quality research. However, in the age of impact measurement, perhaps these institutions could better harness this expertise internally to improve their own sustainability credentials and therefore lead by example. Effective internal communication and a strong sustainability vision could help to translate some of the innovation and expertise developed in these centres of excellence into real-world initiatives on campus. If we can bridge the gap between expertise and action in our own universities to deliver local impact, perhaps we would find ourselves better placed to deliver impact elsewhere.

Professor Carolyn Roberts FRGS FIEnvSc FCIWEM CEnv C.WEM CSci is a ‘Specialist’ on environmental technologies in the Knowledge Transfer Network, Innovate UK’s engagement arm. Earlier in her career, Carolyn was Co-Director of the Centre for Active Learning at the University of Gloucestershire, where she also chaired the Sustainable Development Committee for several years. She is a Vice-President ofthe IES, a former Chair of Society for the Environment and the first Professor of Environment at Gresham College in London.

Robert Ashcroft is the Publications and Policy Officer at the Institution of Environmental Sciences and editor of the environmental SCIENTIST. He holds a BA in Geography from Cambridge University and an MSc in Biodiversity, Conservation and Management from Oxford University. Before joining the IES team, Robert worked as a researcher focusing on biodiversity and nature conservation at the Institute for European Environmental Policy.

- People & Planet, https://peopleandplanet.org/ university-league.

- People & Planet (2014) Green League Guide 2014, https://peopleandplanet.org/dl/greenleagueguide2014.pdf [Accessed 20 November 2015].

- People & Planet, Methodology, https://peopleandplanet.org/ university-league/methodology.

- People & Planet (2015) 2015 League Table, https:// peopleandplanet.org/university-league/2015/tables.

- Institution of Environmental Sciences, Code of Conduct, https://www.the-ies.org/sites/default/files/documents/ code_of_conduct_0.pdf [Accessed 20 November 2015].

- REF2014, Assessment criteria and level definitions, www.ref.ac.uk/panels/assessmentcriteriaandleveldefinitions.

- Rayner, S. (2014) Wicked Problems, Environmental Scientist, 23(2), www.the-ies.org/resources/contentious-issue [Accessed 20 November 2015].