environmental SCIENTIST | Time for a new Clean Air Act? | April 2017

There have been many calls recently about the need for a new Clean Air Act (CAA), from a wide range of leading groups in the environment and public health fields. But are they all asking for the same thing? We asked them to outline why they thought it was important, what they considered to be priorities for new legislation, and their key concerns or opportunities for air quality legislation in light of the Brexit process. We therefore have contributions from the Institute of Air Quality Management, Clean Air Alliance UK and Environmental Protection UK, ClientEarth, the Royal College of Physicians, London Sustainability Exchange and Bright Blue for discussion within this article.

Institute of Air Quality Management

The CAA was primarily designed for local authorities to control emissions from domestic and commercial coal burning. It does little to control air pollution from road traffic, the main source of air pollution in urban areas today, other than enabling fuel quality standards to be set in Regulation, or from decentralised energy plant and gas fired boilers.

The Act also does not address emerging issues, such as the emissions from power generation to meet peak demand for the national grid and to eliminate voltage fluctuations for data centres. The growing use of standby generators, installed for emergency use but used to provide electricity in period of peak demand, is a very recent concern. Therefore, a completely new Act is required to address these new air pollution sources.

It is also time for a new CAA to resolve the inconsistency over where the EU limit values and national air quality objectives apply. It is bizarre that there are two totally separate regimes, both aimed at reducing public exposure to poor air quality, but which come to different conclusions as to where there is an exceedance.

Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 (EA) should be replaced with consolidated Local Air Quality Management duties that combine the useful Local Authority powers from the CAA (such as controlling stack heights), the EA, and the EU Directive. In addition, the Secretary of State and the Devolved Administrations should be required to produce regular Air Quality Strategies (say five yearly). This should include a mandatory review of the air quality objectives based on up to date evidence of the health effects of key pollutants.

There may also be a need for a new duty on local authorities to ensure that air quality does not deteriorate. It may, however, be more appropriate to set a duty to reduce public exposure to air pollution, including vulnerable groups, such as children and older people, rather than focusing on pollution hotspots. The current government planning guidance provides little protection or direction, and strengthening this guidance may be more appropriate than including new duties in a CAA.

Brexit should not be used as an opportunity to water down any air quality legislation, including meeting the recently agreed obligations under the National Emissions Ceiling Directive. In doing so there may be a need for a totally independent, statutory body to be established under a new CAA, similar to the Committee on Climate Change. Its purpose would be to advise national Government on air quality and report to Parliament annually on progress made in reducing public exposure.

EPUK and Clean Air Alliance UK

The Clean Air Alliance UK (CAAUK) was founded by Environmental Protection UK (EPUK), and is a broad partnership of different interests, all with the common aim of improving air quality and working towards healthier air. It comprises of environmental interest groups, companies, public bodies and academic institutions.

The CAAUK and its founder have an additional take on the debate around a new CAA. While EPUK supports the need for a new CAA, especially in the light of Brexit, EPUK and the Alliance are also calling for more high level support and priority to successfully implement current and new legislation on the ground and deliver real health benefits to the public.

Many of the potential levers to improve air quality already exist, but are not used effectively because of split responsibilities between pollution sources and environmental health, both at local government level and national. Why aren’t programmes which affect air quality, e.g. in energy efficiency, transport and ULEV, prioritised for areas with poor air? Air quality needs to be a priority for all bodies which influence it, and this needs high level political support.

The members of the Clean Air Alliance believe that the UK is currently at a tipping point where an acceleration of action on air quality is achievable and desirable, and could have major health, environmental, economic and business benefits. Our aim is to create a new momentum for the urgently needed action to tackle air pollution in our cities and countryside and to clean up the air we all breathe.

While the CAA and other air pollution legislation has been successful at reducing pollution from many sources and provides legal levers for others, it is no longer being implemented effectively. There are also new sources of pollution not covered by the current legislation, and the Brexit process is causing additional uncertainty. By pushing for better implementation, and increasing high level political support to ensure that clean air is a priority, the existing levers (and any new legislation) can be used far more effectively, to improve public health across the UK.

ClientEarth

The government has failed to get a grip with the invisible public health problem caused by air pollution that, according to latest estimates, results in the equivalent of 40,000 early deaths every year. Legal limits for nitrogen dioxide pollution, which were set in the late 1990s and that should have been met in 2010, are still being breached. Even in the case of particulate matter (PM) pollution, where legal limits are being met, we have a long way to go towards achieving much more stringent World Health Organisation (WHO) guideline levels.

The government has failed to get a grip with the invisible public health problem caused by air pollution that, according to latest estimates, results in the equivalent of 40,000 early deaths every year. Legal limits for nitrogen dioxide pollution, which were set in the late 1990s and that should have been met in 2010, are still being breached. Even in the case of particulate matter (PM) pollution, where legal limits are being met, we have a long way to go towards achieving much more stringent World Health Organisation (WHO) guideline levels.

Without the protection of EU laws, we would most likely revert to the ineffective ‘rag-bag’ of domestic laws which are, by the Government’s own admission, not fit for purpose in their current form.

A new CAA is an opportunity to enshrine the right to breathe clean air in UK domestic law and set the ambition to meet safer WHO guideline levels. It would help drive action to tackle modern day sources and make the UK a world leader in clean technology and policy solutions.

A new CAA should preserve obligations currently enjoyed under EU law as a bare minimum, but also significantly improve on EU legislation. A new Act would:

- Retain the objectives under the EU Ambient Air Quality Directive as a minimum safeguard on human health;

- Adopt revised objectives based on WHO guidelines;

- Guarantee the public right to access the courts to enforce its provisions, in accordance with the Aarhus Convention – the procedure must be fast, affordable, allow for substantive review of air quality plans and policies, and provide effective judicial remedies, including fines;

- Consolidate the complex and disparate body of domestic, EU, and international air pollution laws into one coherent and effective piece of legislation;

- Clarify the roles and responsibilities of national government, local authorities, the Mayor of London and the devoted administrations;

- Lay down a national framework for effective Clean Air Zones (CAZ) which phase out diesel and accelerate the shift to zero emission transport;

- Implement the UK's pollution reduction targets for 2020 and 2030 under the Gothenburg Protocol and the newly agreed EU National Emissions Ceiling (NEC) Directive, in order to tackle trans-boundary air pollution;

- Ensure coherence with other relevant policies and legislation, particularly the Climate Change Act and planning guidance;

- Require national, local and city authorities to collect adequate information on air pollution – including data from a minimum number of air quality monitoring stations – and proactively provide the public with that information, including smog warnings during high pollution episodes; and

- Require national, local and city authorities to take measures to reduce exposure to air pollution – particular for vulnerable groups, such as children, older people and those suffering from pre-existing health conditions.

Brexit has led to additional concerns for air quality legislation, and highlights the vital role of the current legislative framework governing air quality in enforcing the right to breathe clean air. In addition to developing and adopting a new CAA, it is vital to enforce the current legal obligations under the Air Quality Standards Regulations (AQSR), to ensure that the order of the High Court is complied with, and that a legally compliant air quality plan is adopted and measures included in it are put in place before 2019.

Another priority is to ’save’ all air quality laws of EU origin. All relevant laws, including the AQSR, must be transferred to domestic legislation through the Repeal Bill. This would require that the Repeal Bill: transfers the directive and the AQSR into domestic law with no weakening amendments; provides that established EU case law applies in the interpretation and enforcement of these laws in the UK; provides for an alternative national equivalent of the European Commission for accountability and enforcement; and gives air quality laws the status of primary legislation so that any future changes to regulations such as the AQSR can only be made through primary legislation i.e. requiring full act of Parliament.

Royal College of Physicians

The intent of the proposed CAA is to provide local and national leaders with the tools and the public mandate to take immediate action on air pollution. The Royal College of Physicians (RCP), along with many other health and environmental groups, will be asking the government to introduce a new CAA. This should aim to tackle the public health crisis of air pollution by consolidating all existing legislation, setting ambitious new emissions targets in line with WHO recommendations and laying out action to achieve those targets.

In particular, the Act should aim to:

- set a UK-wide framework for CAZs in towns and cities to reduce emissions in the most polluted areas (including ships in dock, and airports centrally and regionally);

- introduce policies to disincentivise the use of diesel and incentivise low emission vehicles and active travel (e.g. walking and cycling, scrappage scheme for diesel vehicles, increased taxation on diesel fuel and other incentives);

- require local and national data collection on air pollution from a minimum number of air quality monitoring stations and publicly distribute this data through smog warnings and other methods;

- require national agencies and local authorities to reduce exposure to air pollution amongst vulnerable groups such as children, older people and those with pre-existing health conditions, through town and transport planning and the provision of health information; and

- align with the Climate Change Act to ensure joined up action.

With regard to the challenges or opportunities posed by Brexit, the RCP believes that frameworks that underpin health protection must be replaced by equivalent or even stronger safeguards. The RCP has voiced particular concern to maintain strong EU air quality standards against pressure to weaken them. The EU has played a significant role in driving measures to control air pollutants and has provided a vital enforcement regime, allowing the UK to be held to account on meeting air quality targets. For example, the NEC Directive sets binding emission ceilings to be achieved by each member state and covers four air pollutants: sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, non-methane volatile organic compounds and ammonia. Air pollution does not recognise national boundaries and given the important role that transboundary sources play in local air pollution, it is essential that the UK continues to work with the EU in responding to the challenges posed by air pollution.

London Sustainability Exchange

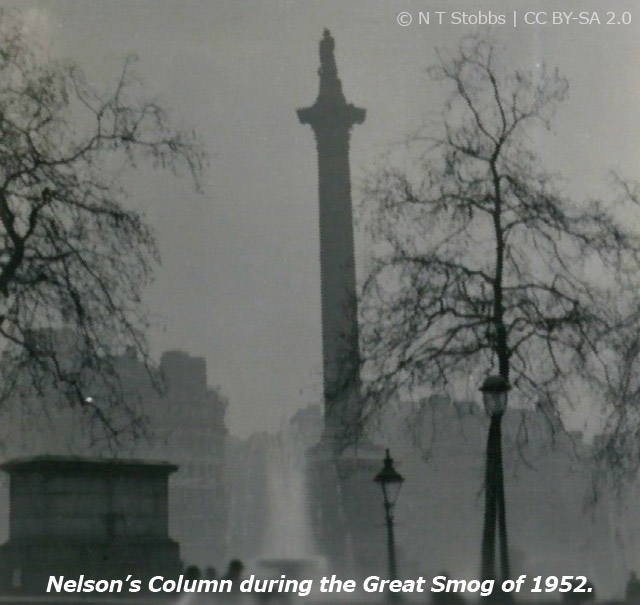

The great smog of 1952 led to the development of the 1956 CAA, which went on to save the lives of many people. Despite the uncertainty of Brexit, we see this as an exciting opportunity to bring in stronger and tighter air pollution standards, making the UK a leader in air quality legislation. The new CAA should take into consideration several aspects, such as the introduction of cleaner vehicles, whether by access restrictions or emission charges, and other effective measures, such as the introduction of CAZ. We want to find a consensus between all stakeholders to find solutions which will be mutually beneficial.

Opportunities that lie ahead for a new CAA:

- Establish air quality objectives that are compliant with the stronger WHO recommendations. Mandate local, city and national authorities to monitor pollution adequately.

- Define effective interventions to tackle air pollution at local, city and national levels. Promote acceptance, understanding and confidence among the public opinion and coordinate actions.

- Introduce fiscal incentives to clean up polluting air, to phase out the most polluting vehicles and other sources of pollutants, and promote cleaner means of fuel and energy. Incentivise the adoption of sustainable transport infrastructure, such as cycling and walking.

- Planning framework and guidance to include a duty to reduce pollution.

- Promote public information about pollution by text alert and other tools that help people to avoid pollution hotspots.

‘Pollution busting’ will require significant public engagement, to encourage attitudinal change, behavioural change and adaptation to minimise the health impacts of pollution.

Bright Blue

The UK is currently failing to meet the legal limits for air pollution. Following a defeat at the High Court, the Government now has until April 2017 to produce a new draft plan. Supported by a range of organisations and the Chair of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Select Committee, Bright Blue has been campaigning for greater funding and powers to be devolved down to cities to enable them to set up their own low emission zones in pollution hotspots. This is urgently needed: our research has found that, last year, over 40 per cent of local authorities breached the legal limits. Yet, under the old plan, just five cities were mandated to set up CAZ.

Brexit creates the opportunity for the UK to be more ambitious on air quality. Forty thousand premature deaths per year are linked to air pollution. But this major public health problem will not be resolved solely by making the UK compliant with the EU limits; the WHO guidelines show these are not sufficient to prevent medical harm.

A new CAA should therefore enable local authorities to take bold action and be underpinned by the best scientific evidence for when pollution causes health problems. This approach would deliver multiple benefits for the UK. As well as improving public health and reducing costs for the NHS, it would provide a stimulus to the automotive sector. A strong air quality framework would incentivise owners of older, diesel vehicles to purchase new electric vehicles. Increasing domestic demand would help consolidate the UK’s position as the largest market for electric vehicles in Europe. This would complement the forthcoming industrial strategy.

The first CAA in 1956 was passed by a Conservative Government. A new CAA would be an opportunity for this Conservative Government to demonstrate the UK’s commitment to a stronger, healthier environment.

Summary

There were clear areas of consensus around the need for legislation which reflected current sources of pollution, especially road transport and diesel, and new stationary sources of pollution, as well as continued protection for traditional industrial plants. Brexit is thought to pose a risk to environmental legislation, but it could also be seen as a potential opportunity to improve air quality laws, provided substantial safeguards are included, and key weaknesses to enforcement and the legal landscape are addressed. There was also a call by the Clean Air Alliance UK and Environmental Protection UK to consider how to make current and new legislation more effective, by identifying what more needs to be done, and who else needs to be involved, to ensure it has the high level political support and priority necessary to implement successfully on the ground and deliver real health benefits to the public.

Sarah Legge is Director of SLH Environmental Ltd, an independent consultancy specialising in air quality and sustainable transport. She has extensive experience, including previously working as Head of Air Quality at the Greater London Authority. Sarah serves on the IAQM Committee and is Chair of the EPUK Air Quality Committee.

This article is taken from the April 2017 edition of the environmental SCIENTIST. It was written before the 2017 draft Air Quality Plan was published.