environmental SCIENTIST | Counting on Net Gain | September 2024

Ellie Savage and Ethny Childs consider the challenges, opportunities and next steps for this ambitious policy.

Mandatory biodiversity net gain (BNG) came into force in England on 12 February 2024 for major developments and on 2 April 2024 for small sites. It requires a 10 per cent increase in biodiversity post-development – although it is worth noting that some local planning authorities have set a higher minimum requirement – meaning that natural habitats are left in a better state than before development. Biodiversity is measured in units, which are calculated using the statutory biodiversity metric.1

A joint project called ’Mandatory biodiversity net gain in practice’ by the IES and Association of Local Government Ecologists (ALGE) sought to establish an initial understanding of how BNG was working on the ground.2 The purpose of the project was to identify good practice that could be adopted by practitioners and common challenges that can be addressed by decision-makers.

The first part of the project was the distribution of an online survey, running between 1 and 26 August 2024. There were 142 responses, of which 89 per cent came from IES or ALGE members. Most respondents work in planning (23 per cent), ecology (19 per cent) and environmental consulting (19 per cent). The survey included questions on how well BNG was working in practice, a request to rate potential challenges and a discussion of possible solutions. The survey also asked respondents whether they were willing to participate in a short interview, which would form the second part of the project.

Credit: © I-Wei Huang | Adobe Stock

How is the policy working in practice?

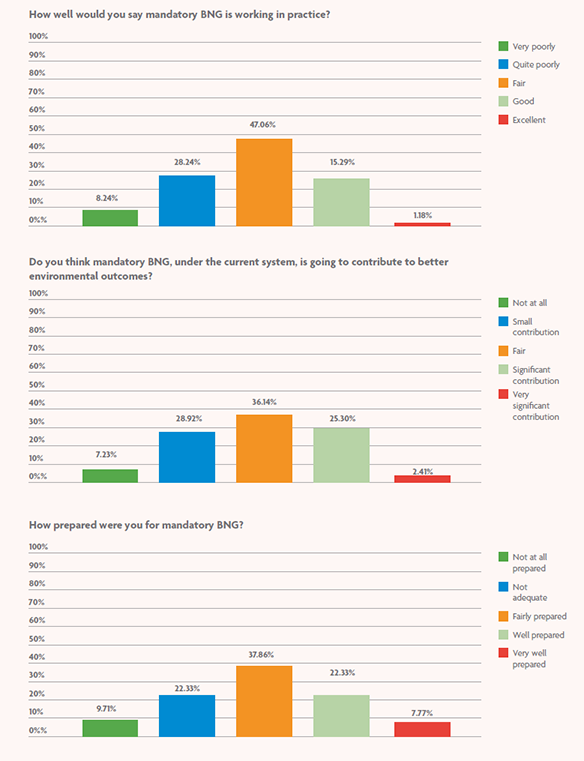

Several closed questions asked participants about their general experience of BNG. Responses included the following (see Figure 1):

- Nearly 66 per cent thought BNG was working at a fair, good or excellent level in practice, with just over 33 per cent stating it was working quite poorly or very poorly.

- There was a range of opinions on whether BNG would lead to better environmental outcomes. Around 36 per cent said that it would make a fair contribution, a further 36 per cent a small or no contribution, and 28 per cent a significant or very significant contribution.

- Around 68 per cent of participants were fairly, well or very well prepared for BNG, with only 10 per cent stating that they were not at all prepared.

These results show highly mixed experiences and perspectives of BNG across the planning and environmental sectors. At the more extreme ends of opinion there is a clearer swing with a significant proportion (8.2 per cent) having a very negative view of BNG compared to 1.2 per cent who have a very positive view.

|

| Figure 1. Survey responses. (Source: IES) |

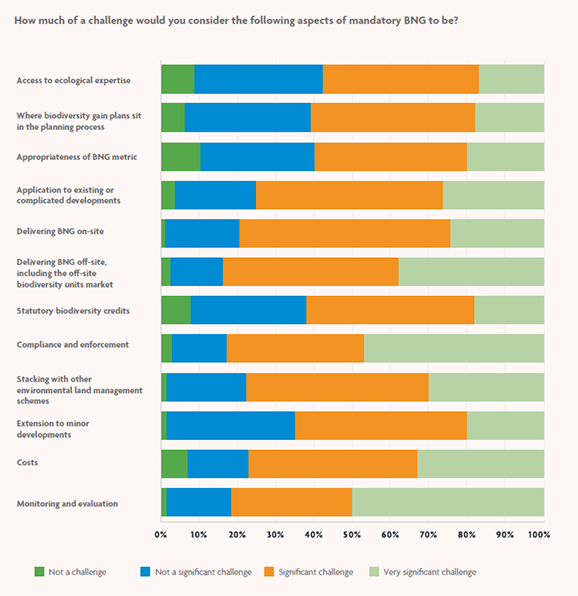

The survey also sought to understand how much of a challenge aspects of BNG were. All 12 aspects of the policy presented were rated as a significant or very significant challenge by over half the participants (see Figure 2).

|

| Figure 2. Survey responses showing the level of challenge presented by biodiversity net gain. (Source: IES) |

Delivering BNG off-site (including through the biodiversity market), compliance and enforcement, and monitoring and evaluation were rated as key challenges, with over 80 per cent of participants ranking them as a significant or very significant. Delivering BNG on-site was rated as a significant or very significant challenge by 79 per cent of respondents.

More information required pre-planning

The survey results show confusion around how BNG interacts with the planning process. Before planning permission can be granted for a development, the applicant must provide certain BNG-related information, such as the pre-development biodiversity value of the site and details of any irreplaceable habitats.3

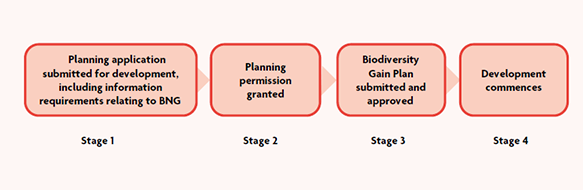

However, applicants do not need to provide a post-development biodiversity metric calculation or information on how they will achieve the 10 per cent BNG gain – called the biodiversity gain plan – to secure planning permission. Indeed, the Biodiversity Gain (Town and Country Planning) Regulations 2024 state that the biodiversity gain plan should not be submitted until the day after planning permission is granted.4 It is, however, regarded as good practice to submit a draft biodiversity gain plan at the planning application stage.5 Once planning permission has been granted, a biodiversity gain plan must be submitted and approved by the local planning authority (LPA) before construction can commence (see Figure 3).

|

| Figure 3. Stages of the biodiversity net gain application process. (Source: IES) |

Stages of BNG application process (Source: IES)

The survey results suggest that, in practice, there is a lack of clarity and inconsistent application of the biodiversity gain plan. Participants were asked whether, in their experience, the biodiversity gain plan had been produced before or after planning permission. Around 50 per cent thought it was produced before planning permission, 23 per cent after and 27 per cent were unsure. Some respondents added that it varied or that a draft gain plan was used initially and finalised following planning permission. However, there was a significant consensus on how the system should work, with 79 per cent saying they thought that the biodiversity gain plan should be produced for the planning application.

Several comments provided more detail on what biodiversity information should be produced at an earlier stage: one participant stated that ‘planners [should] only determine applications after detailed ecology surveys, not just a preliminary ecological appraisal… [We should] ensure BNG plans are also agreed pre-planning’. Another respondent advocated for ‘amend[ing] statutory guidance to insist on post-development calculations before determination’, while another wrote that:

‘The only questions in the gain plan that need answering after determination concern the confirmation of buying national credits and linking the off-site parcel of registered land to the consented planning application. These two questions could form part of a post-determination, specifically numbered discharge condition instead.’

One participant who thought that the biodiversity gain plan should be produced after planning permission qualified that the ‘eight-week determination period is totally excessive. It should be agreed in principle before’.

Others argued that there is a wider problem with biodiversity and BNG not being integrated throughout the design and development process, leading developers to consider BNG as a problem to be resolved post-design through offsetting. Integrating environmental professionals into project design teams and using environmental impact assessment (EIA) as a tool to support design has long been called for to support better environmental outcomes and alignment with the mitigation hierarchy.6 Exploring the interaction between the EIA process and delivering BNG could be a key part of increasing the impact of BNG measures and ensuring compliance.

Credit: © Iryna | Adobe Stock

On- and off-site biodiversity net gain

Developers should always seek to achieve on-site gains first but can use a mixture of gains to achieve 10 per cent BNG; statutory biodiversity credits should only be sought as a last resort. Only three applications for credits have been made in the first six months, which is significantly below expectations and points to serious delays within the BNG regime. Survey participants were asked to give their experiences of on-site gains, including what has and has not worked well.

A common theme was the concern that on-site BNG delivered poorer environmental benefits than off-site BNG. One reason for this was that on-site gains are often in the hands of developers, who may not take the appropriate care to implement and monitor them. Previous research has also shown the significant risk of on-site gains falling into governance gaps.7 Governance gaps relate to instances where conditions are in place that expose the gains to a high risk of non-compliance. For this study, the factors that placed an on-site gain at such a risk included a lack of registration, higher exposure to humans and pets, potential tensions between human and ecological needs for the space and a lack of experience by property managers in managing for biodiversity.

There were comments regarding on-site gains being subject to loopholes, shortcuts or being gamed. Examples included the increase in small-scale self- or custom builds (which are exempt from BNG) and the use of private gardens for BNG purposes (the outcomes of which cannot be guaranteed).8 Research by law firm BDP Pitmans suggests that these types of policy loopholes are a critical issue, and that abuse is widespread.

Survey respondents suggested that developers were also more likely to default to easy enhancements such as tree planting, which may not be appropriate for the site. One potential solution was additional guidance for relevant stakeholders on the main biodiversity enhancements, their benefits and how they suit certain landscapes. One survey respondent noted that it is ‘challenging to get developers to understand that they must protect those areas and manage them for a long time’, while another remarked that ‘we have seen these schemes ending up coming back to specialist BNG operators, as the developer has not been equipped to undertake the habitat production’.

Another common issue with on-site gains was the higher prevalence of small or randomly situated pockets of gain sites instead of the larger, joined-up sites for nature favoured by the Lawton Principles.9 Suggestions to improve the quality of on-site gains included an on-site BNG register (similar to that for the off-site system) and the introduction of a mechanism to value ecological connectivity. Specifically, one respondent stated: ‘I think off-site contributions to larger biodiversity projects with robust management controls should be promoted over small-scale habitat creation that may fail through poor enforcement’.

Several responses discussed the difficulty of realising on-site gains on small sites: ‘1- to 2-house developments with limited shared open space’ are not comparable to ‘large housing developments on farmland’. Most small sites therefore need off-site delivery, but the costs and requirements associated with this are high and these developments often have limited funds.

Credit: © drhfoto | Adobe Stock

Delays in the off-site BNG market

Survey participants were also asked about their experiences with off-site BNG. Around 20 per cent had experience with units purchased on the biodiversity market and around 20 per cent had experience of off-site units on existing developer-owned land. Participants were also asked to give their experiences of off-site gains. The responses varied, with some experiencing serious problems with the market and others saying that it was working well. This suggests that the market may not be consistent across the country.

For those who had a negative view of the biodiversity market, the key issue was the pace at which LPAs were approving off-site units (i.e. approving habitat management plans and legal agreements). Habitat banks in particular are facing LPA approval delays. This is causing knock-on delays for developers, with the number of approved off-site units not meeting demand. According to one respondent, ‘At the moment we have over 120 off-site owners interested in providing credits, but there have been no buyers due to low activity in planning consents and applications’. One suggested solution for speeding up the process was the establishment of a central BNG habitat management plan assessment:

‘The main issue seems to be securing legal agreements for off-site schemes, which is seriously holding up availability. However, there are plenty of units in the marketplace, so this will become less of an issue over time.’

However, many respondents saw off-site gains, where available, as an easier and higher-quality option than on-site gains, albeit with a higher price tag. For example, one respondent said that ‘this seems to be the best option: it's on a register, it's covered by legal agreements, it delivers larger ecologically connected areas’. Yet there were also concerns that not all off-site BNG unit providers were of high quality. One participant warned of a ‘“race to the bottom”, with for-profit organisations trying to sell units as cheap[ly] as possible with the objective being profit rather than environmental outcomes’, and arguing there was a need for better regulation. That said, there is also recognition that there are good providers. As one participant stated:

‘The market has worked well when engaging with top ecology-based firms such as Environment Bank that are able to provide a fully funded and ecological[ly] certain BNG unit purchase so that it fully de-risks it for the developers and the LPAs.'

Credit: © Savo Ilic | Adobe Stock

Monitoring and enforcement capacity

As well as being rated as a significant or very significant challenge by almost all respondents, the importance of securing good monitoring and enforcement were brought up throughout the survey. As one person remarked: ‘It is pointless landscaping, tree planting and pond making at sites if these are not maintained accordingly’. Many respondents were concerned that monitoring and enforcement will not take place. This risk was also identified in a recent report by the National Audit Office: LPAs only have a discretionary duty to undertake monitoring and enforcement.10

Participants were also specifically asked how they were preparing to monitor and enforce gains, what challenges they anticipated and what the potential solutions were. A common response theme was the lack of clarity over who was responsible for monitoring and enforcement and how they should be funded. Many of the survey participants were concerned about the lack of capacity within LPAs, with some suggesting there would need to be an increase in the number of planning, legal and ecology specialists to effectively monitor and enforce BNG:

‘The two of us in the LPA ecology “department” are already spread thin with the workload; I am not sure how realistic the delivery of the monitoring and enforcement of all the implemented BNG plans will be. I am not sure how this would be resolved without more staff involved that could adequately assess it.’

Others suggested that existing staff could be trained to deliver simple ecological monitoring tasks – for example, using Local Environmental Record Centres. Some thought that funding should be made available for monitoring to be undertaken by external bodies. Several respondents mentioned the need for funding to be secured up front – for instance, through reflecting it in the price of BNG units. A few respondents mentioned the need for improvement of LPA databases to enhance monitoring and enforcement. One respondent suggested creating an open register or map of delivered credits, with the potential for local communities to play a role in monitoring local sites.

When discussing enforcement and penalties, there was a range of suggestions, with some advocating for stiffer penalties for non-compliance and for the setting up of a BNG watchdog to arbitrate and penalise, especially the ‘unregulated habitats bank market’. Others suggested motivating developers to deliver ongoing habitat management – for example, through a grading scheme of company commitment to BNG.

More robust post-project monitoring is needed to support improved understanding of the effectiveness of interventions and the environmental impacts of developments. Making monitoring data openly accessible and interoperable will support better evidence to feed into EIAs and provide more effective mitigation and BNG measures.

Conclusion

Six months in, the survey results indicate that BNG is working well for most practitioners. Yet it also tells a more complicated and developing tale. Many respondents remarked that it was difficult to definitively answer questions at this early stage, and that future research may tell a different story. However, it was clear that there are some significant issues that should be addressed.

- More biodiversity gain information needs to be produced at the planning application stage;

- Some on-site BNG is at risk of not providing significant environmental benefits, and stricter regulation and guidance need to be provided;

- The off-site BNG market is facing serious delays with the need to speed up LPA approvals; and

- LPAs also need more capacity for monitoring and enforcement, which are critical if BNG is to achieve its aims.

The Government has committed to transforming the planning system to unlock development to build 1.5 million new homes and a generation of new towns. This wave of development will change the face of the country, and it must be done in a way that is right for nature. The Government has also recognised the dire funding problems facing local authorities, and addressing this will be at the heart of ensuring that BNG takes place in communities, not just on a spreadsheet.

As it stands, 33 per cent of survey participants think that BNG will make a small or no contribution to environmental outcomes. Improvements to practice are critical if BNG is going to play its part in unlocking the environmental improvement across the country that we urgently need to protect biodiversity, restore ecosystem health and meet our national and international commitments.

Download the article to read it as a pdf

Further Reading

- Wentworth, J. (2024) Biodiversity Net Gain. Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology, POSTnote 728. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/POST-PN-0728/POST-PN-0728.pdf (Accessed: 22 September 2024).

- Natural England (2024) BNG lessons learned with Local Planning Authorities. https://naturalengland.blog.gov.uk/2024/07/23/bng-lessons-learned-with-local-planning-authorities/ (Accessed: 12 September 2024).

- Green Finance Institute (2024) Biodiversity net gain: a roadmap for action. https://hive.greenfinanceinstitute.com/gfihive/insights/biodiversity-net-gain-a-roadmap-for-action/ (Accessed: 12 September 2024).

Ellie Savage is a Policy Officer with the IES. She is responsible for supporting the work of the IES’s Environmental Policy Implementation Community (EPIC). Before joining the IES, Ellie led on local government policy and research at a climate change and democratic engagement charity. She has a BA in Politics and Economics from the University of Sheffield and is interested in how to influence environmental policy at the local level.

Ethny Childs is Communities and Partnerships Lead at the IES. Recognised on the 2024 ENDS Power List, Ethny is a trustee for Charityworks, sits on the Specialist in Land Condition (SiLC) board and holds positions on the steering groups for the Professional Bodies Climate Action Charter, the Equator Programme and the Media Trust's Communicating Climate Programme.

References

- Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2023) Statutory biodiversity metric tools and guides. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/statutory-biodiversity-metric... (Accessed: 13 September 2024).

- Institution of Environmental Sciences (2024) New Biodiversity Net Gain in Practice project launched. https://www.the-ies.org/news/new-biodiversity-net-gain (Accessed: 13 September 2024).

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government and Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (2024) Biodiversity net gain. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/biodiversity-net-gain#para11 (Accessed: 11 September 2024).

- UK Statutory Instruments (2024) The Biodiversity Gain (Town and Country Planning) (Consequential Amendments) Regulations. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2024/9780348254419 (Accessed: 15 September 2024).

- Durkin, P. and Baker, J. (2024) Mandatory Biodiversity Net Gain in England: A Guide. Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management, Construction Industry Research and Information Association, and Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment. https://cieem.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/BNG-Technical-Guide-2024-1.pdf (Accessed: 11 September 2024).

- Institution of Environmental Sciences (2023) Reframing EIA: a tool for better design for people and planet. https://www.the-ies.org/resources/reframing-eia-tool-better (Accessed: 11 September 2024).

- Rampling, E.E., zu Ermgassen, S.O.S.E., Hawkins, I. and Bull, J.W. (2023) Achieving biodiversity net gain by addressing governance gaps underpinning ecological compensation policies. Conservation Biology, 38 (2), e14198. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.14198 (Accessed: 13 September 2024).

- ENDS Report (2024) Government moves to close BNG ‘loophole’ as industry warns of wider risk of developer exploitation. https://www.endsreport.com/article/1886038/government-moves-close-bng-loophole-industry-warns-wider-risk-developer-exploitation (Accessed: 24 September 2024).

- Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2010) ‘Making space for nature’: a review of England's wildlife sites published today. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/making-space-for-nature-a-review-of-englands-wildlife-sites-published-today (Accessed: 22 September 2024).

- National Audit Office (2024) Implementing statutory biodiversity net gain. https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/implementing-statutory-biodiversity-net-gain/ (Accessed: 9 September 2024).

Header image © William | Adobe Stock